Comic Book Guy is my favorite Simpsons character, and I love to listen to him discourse about “Radioactive Man No. 1” and other comic collectibles as he interacts with Bart and Millhouse in the Android’s Dungeon and Baseball Card Shop. But who knew that he would become a harbinger of a 21st century obsessed with superheroes and the minutiae of their complicated lives? Once upon a time, in an era that now seems far, far away, the Star Wars movies and the Marvel Universe drew much of their energy from classic fairy tales and myths. Now, like it or not, the stories they told — and continue to tell — have become our fairy tales and myths.

Recognizing this, last year I read six sumptuous comics collections — three from Penguin Classics, three from the Folio Society — devoted, with some overlap, to four of the most beloved Marvel characters: Black Panther, Spider-Man, Captain America and the Hulk. I honestly hoped to recapture some of the excitement I would have felt about them at the age of 10. Alas, as an adult my reaction mirrored that of a dejected Coleridge when one night he looked up at the stars and the crescent moon: “I see, not feel, how beautiful they are.”

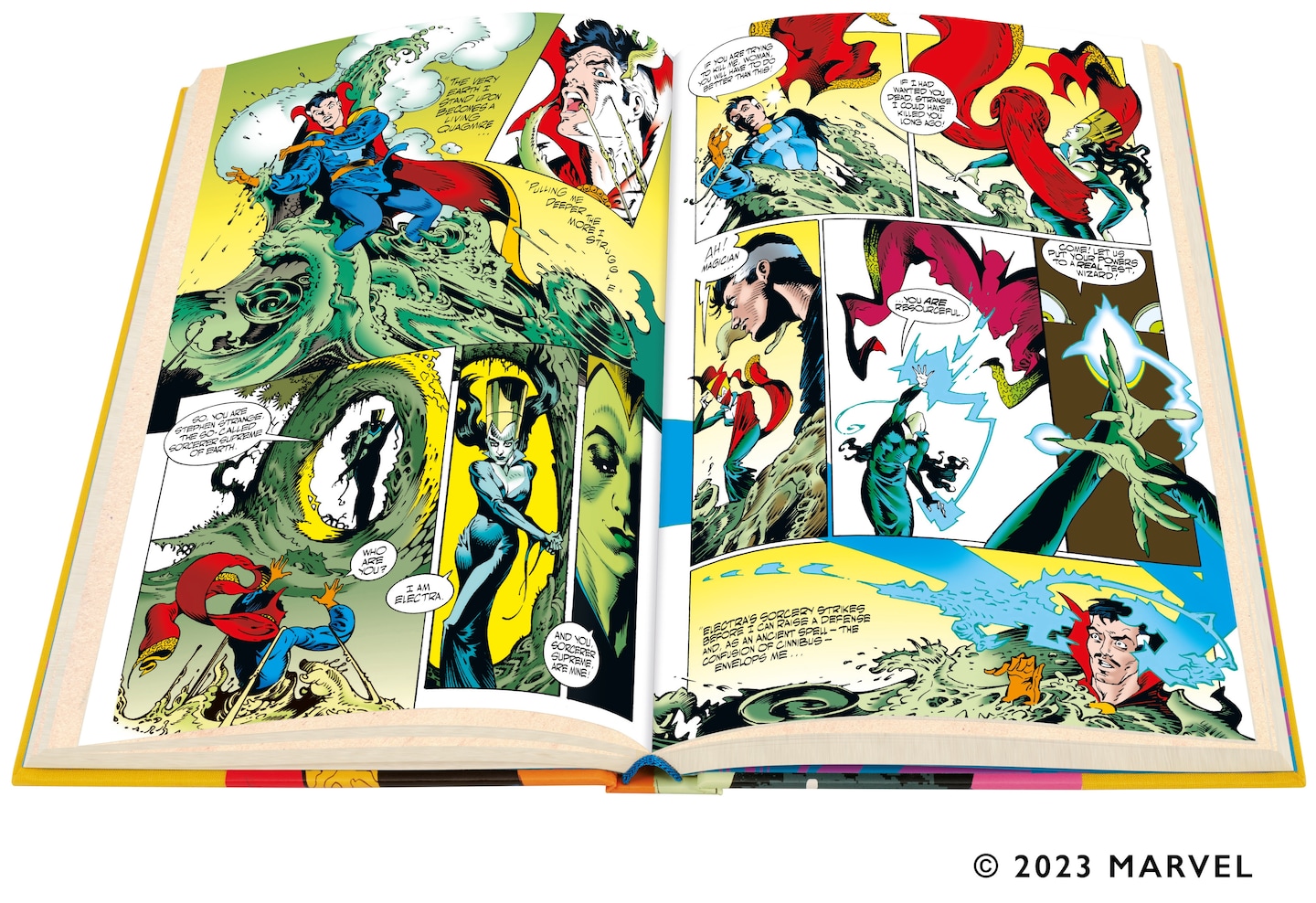

These same two publishers have just issued similarly lavish volumes about other Marvel superheroes. Penguin focuses on the early years of the Fantastic Four, the X-Men and the Avengers; Folio gives us a broader, more deluxe survey of the career of Doctor Strange, master of the mystic arts. As before, these collections are mainly intended for general readers rather than confirmed fans. Penguin provides introductory essays; superb analyses by the series editor, Ben Saunders; and extensive bibliographies. The Doctor Strange collection — like others in Folio’s series — is compiled and introduced by Roy Thomas, Stan Lee’s successor as head of Marvel as well as a versatile comics writer himself.

This time, I abandoned any attempt to recapture my boyhood sense of wonder. Loosely speaking, Marvel’s early superhero adventures are all pretty much the same. Open any of these books and you will find an action-oriented confrontation pitting a group of characters with extraordinary powers against a seemingly invincible adversary. Saunders, who teaches at the University of Oregon, even outlines the standard pattern of a typical X-Men comic: In the opening pages the X-Men show off their powers to Professor Xavier and squabble a bit. The venue then shifts to the sudden appearance and consequent depredations of some supervillain, human or otherwise. Various battles with said enemy — who initially seems unbeatable — quickly ensue, leading to the capture or imminent destruction of the once-cocky X-Men, at which point some oversight on the part of the villain or some last-minute razzle-dazzle allows victory to be snatched from the jaws of defeat. The victory is, of course, only temporary, because the monster-alien-robot-mad scientist — Magneto is a particular favorite — nearly always escapes, so that he, she or it can return to seek vengeance another day and cause further mayhem.

While adults may quickly grow bored with this repetitiveness, kids love it: They’d feel shortchanged if the Thing didn’t exclaim, “It’s clobberin’ time!” On one level, then, these adventures seemingly work best for young and inexperienced readers. But for adults there are other ways to approach these comics than through their plots. As many critics have pointed out, Marvel superheroes quite obviously reflect or critique the attitudes and prejudices of postwar America. The Fantastic Four could be one of the era’s loving and bickering TV sitcom families, while the mutant X-Men represent the insulted, injured and marginalized of society. The Avengers started out as a counter-blast to DC Comics’ Justice League of America but initially spotlighted mainly B-list superheroes. The roster would change dramatically over the years, growing increasingly diverse and inclusive. At first, Doctor Strange might appear something of an outlier, but the Sorcerer Supreme fits right in with the supernatural-fiction boom of the 1970s and ’80s and, through an ongoing emphasis on altered states and cosmic visions, with that period’s passion for the psychedelic.

These Silver Age superheroes initially appeared when psychoanalysis was all the rage, when most people worried more about being alienated than they did about aliens from space. Hence the insistence, now a tiresome clich? of the genre, on the self-doubts and anguished souls of their protagonists. Consider the Fantastic Four. Ben Grimm, transformed into a hulk-like monster known as the Thing, regularly troubles deaf heaven with his bootless cries: Why must I be different from other men? The Human Torch, a.k.a. teenager Johnny Storm, suffers the hormonal agonies and impulses of male adolescence. His older sister, Sue Storm, a.k.a. Invisible Girl (later renamed Invisible Woman), feels insecure, worrying that she doesn’t contribute enough to the team. Its leader, Reed Richards, frequently comes across as a more colorfully appareled version of the Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, just one more overworked exec weighed down with responsibility. He eventually marries Sue, who has to live with people calling her husband Mister Fantastic.

Still another way to approach these comics is to see them as attempts to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork. In this regard, one needs to start with the “Marvel Method,” which essentially allowed — compelled? — some pictorial artists to function as writers. Editor in chief Stan Lee would often give Jack Kirby the precis of a plot, then leave it to the artist to lay out each page, sketch the appropriate pictures, and even write the narration and dialogue. (Other staffers would generally do the coloring and lettering.) While Lee seems to have suggested that the Fantastic Four combat Galactus, who traipses around the cosmos sucking the energy from entire planets, Kirby’s genius led him to add one of the most surreal and haunting figures in comic history, the Silver Surfer. As the herald of Galactus, this sleek silver being skims through the universe, dodging meteors, while riding his shiny surfboard. Though he appears to be an android, it turns out that the Surfer — like everyone else in comics, or American literature for that matter — suffers from loneliness. It is through his sympathy for the human race that Earth is eventually saved from destruction.

Lee and Kirby also practice a version of what the playwright Bertolt Brecht called — neatly enough — the alienation effect: They don’t take these comics altogether seriously. They approach them with a certain wry, tongue-in-cheek amusement rather than intense emotional involvement. Instead, each page bristles with dynamic, even conflicting semiotic signals. Rather than a succession of square panels for the layout, one finds horizontal and slanted panels, close-ups and distance shots, full-page and even double-page tableaux, improbable and garish colors. The eye moves restlessly from narration to dialogue to picture, and back again, such that one never totally loses oneself in the action. Editorial footnotes further break up the narrative spell. There are metafictional cross-references to other comics — at one point the Thing reads about the Hulk. Lee and Kirby occasionally appear as themselves. And there’s considerable in-house humor, as when Doctor Strange visits the city of Ditkopolis, a tip of the hat to artist Steve Ditko. A letters page even allows fans to interact with the Marvel bullpen, request further appearances of a favorite character — such as that Byronic prince of Atlantis, Namor the Sub-Mariner — and suggest ideas for a series’s future development. In multiple ways, the reader co-creates the Marvel universe.

Looked at in 2023, these early superhero adventures, largely taken from the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, exhibit an innocence and Mad Magazine-like insouciance unknown to the existentially bleaker, often more highly sexualized comics of recent years. But of course the latter aren’t meant to be read, traded and argued over by 10-year-old kids. Today, if Marvel comics are read at all, it must be very carefully, so as not to crease or damage a valuable investment. You certainly wouldn’t want Comic Book Guy to glance at your collection and say, in that drippingly sarcastic voice of his, “Worst. Copies. Ever!”